Barrett’s esophagus isn’t something most people hear about until they’re diagnosed. But for those with long-term heartburn, it’s a silent warning sign - a change in the lining of the esophagus that can, over time, turn into cancer. The good news? We now have powerful tools to stop it. The bad news? Many people don’t know they’re at risk, or they’re unsure what to do next.

What Exactly Is Barrett’s Esophagus?

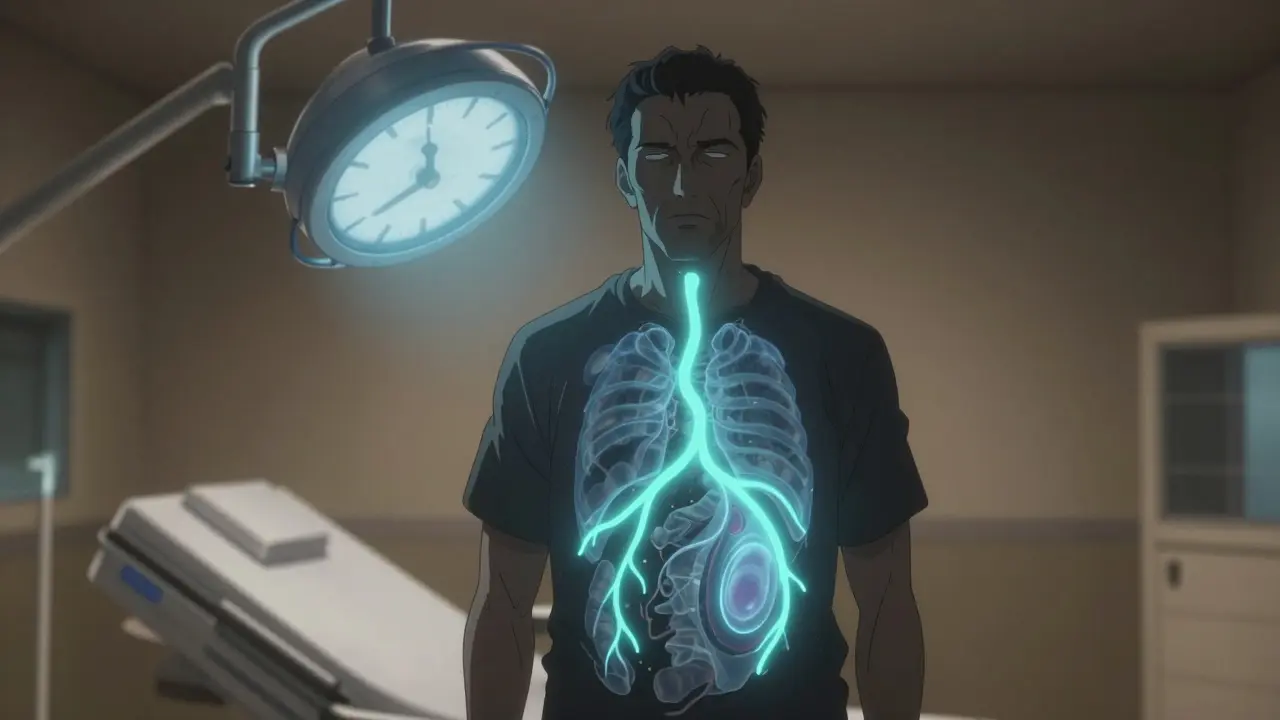

Barrett’s esophagus happens when the normal tissue lining your esophagus - the tube that connects your throat to your stomach - gets replaced by tissue that looks more like the lining of the intestine. This change, called metaplasia, is your body’s response to years of acid reflux. It’s not cancer. But it’s the only known precursor to esophageal adenocarcinoma, a type of cancer that’s become far more common over the last 50 years.

It’s not rare. About 5.6% of U.S. adults have it - that’s over 3 million people. But only a small fraction of those with chronic GERD develop it. If you’ve had heartburn several times a week for five years or more, your risk jumps. Men over 50, especially white men, are at highest risk. So are people with abdominal obesity, smokers, or those with a family history of Barrett’s or esophageal cancer.

What makes it dangerous isn’t the metaplasia itself - it’s what can come after. Over time, this abnormal tissue can develop dysplasia: abnormal cell changes that are precancerous. And once dysplasia appears, the clock starts ticking.

The Real Risk: Progression to Cancer

Most people with Barrett’s esophagus will never get cancer. But the risk isn’t zero. For those with no dysplasia, the chance of developing esophageal cancer is about 0.2% to 0.5% per year. That sounds small - until you realize that over 20 years, that adds up to a 4-10% lifetime risk.

But if you have low-grade dysplasia (LGD), your risk jumps to 5 times higher. And if you have high-grade dysplasia (HGD)? Your risk shoots up to 23-40% per year. That’s not a slow burn - that’s a red flag.

Not all Barrett’s is the same. Long-segment Barrett’s - where the abnormal tissue is more than 3 centimeters long - carries a much higher risk. So does persistent acid exposure. Even if you’re on proton pump inhibitors (PPIs), if your reflux isn’t fully controlled, your cells keep getting damaged. One study found that people with ongoing acid exposure despite PPIs have 7.3 times higher risk of progression.

And here’s something surprising: alcohol doesn’t increase your risk. But smoking does. So does caffeine - weekly intake has been linked to higher progression rates. And if you’ve had colon polyps (adenomas), your risk also goes up.

Ablation: The Game-Changer for Dysplasia

For decades, the only option for Barrett’s with dysplasia was surgery - removing the esophagus. That’s a major operation with lifelong consequences. Now, we have endoscopic ablation: procedures done through the mouth, no cuts needed.

Radiofrequency ablation (RFA) is the gold standard. It uses controlled heat to destroy the abnormal tissue. The HALO360 catheter treats the whole circumference of the esophagus; HALO90 targets visible lesions. In clinical trials, RFA cleared intestinal metaplasia in 77.4% of patients and dysplasia in 87.9% within a year. Real-world data shows even better results - up to 91.5% complete eradication.

It’s not perfect. About 6% of patients develop strictures - narrowing of the esophagus - requiring dilation. Some need multiple sessions. One patient on Reddit described needing four dilations after three RFA treatments: “The chest pain during dilation was worse than the original Barrett’s symptoms.” But for most, the trade-off is worth it.

Other Ablation Options: Cryoablation, PDT, and EMR

Cryoablation uses extreme cold - nitrous oxide cooled to -85°C - to freeze away abnormal tissue. It’s newer, and studies show it clears dysplasia in about 82% of cases. The big advantage? Lower stricture rates. For patients who’ve had prior strictures, cryoablation is safer than RFA. It’s also less likely to cause pain during recovery. But it’s less effective at erasing the underlying metaplasia - 65% compared to RFA’s 91%.

Photodynamic therapy (PDT) was used years ago. You get a light-sensitive drug, wait 48 hours, then shine a laser on the esophagus. It works - 77% dysplasia clearance - but it’s messy. You can’t go in the sun for weeks. And 17% of patients develop strictures. Today, it’s rarely used.

Endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR) isn’t ablation - it’s removal. If you have a visible nodule or bump in the esophagus, doctors can lift and cut it out. It’s great for diagnosing and removing early cancers. Success rate is 93% for small lesions. But it carries a 5-10% risk of bleeding and a 2% risk of perforation. It’s usually done before ablation, not instead of it.

Cost, Access, and Real-World Challenges

RFA costs about $12,450 per session. Cryoablation is cheaper - around $9,850. But RFA often needs fewer repeat sessions. Over five years, both end up costing about the same per quality-adjusted life year. Insurance usually covers them if you have confirmed dysplasia.

But access isn’t equal. In academic hospitals, nearly all offer ablation. In rural clinics? Only 42% do. That’s a problem. People in rural areas are 2.3 times more likely to die from esophageal cancer than those in cities.

And here’s a hidden issue: misdiagnosis. Pathologists disagree on low-grade dysplasia. Community pathologists only agree with experts 55% of the time. That means some people get unnecessary treatment. Others get missed. That’s why experts now recommend having your biopsy reviewed by a GI pathologist who sees Barrett’s regularly.

What Happens After Ablation?

Ablation isn’t a cure-all. You still need lifelong surveillance. Even after your tissue looks normal, Barrett’s can come back. Studies show recurrence rates of 8-25% within three years. That’s why you need endoscopies every year or two.

And you still need to manage reflux. High-dose PPIs - like esomeprazole 40mg twice daily - cut recurrence risk by more than half. Lifestyle changes matter too: lose weight, quit smoking, avoid late-night meals, and reduce caffeine.

Some patients report dramatic improvements. One woman on a support forum said her chronic cough from reflux disappeared after cryoablation. “Worth every uncomfortable moment,” she wrote.

What’s Next? AI, Biomarkers, and Better Screening

The future is getting smarter. AI tools are now being tested to spot dysplasia during endoscopy. Google Health’s system detected lesions with 94% accuracy - better than most human endoscopists. That could mean fewer missed cases.

And soon, we may not need biopsies everywhere. A blood or saliva test for TFF3 methylation - a molecular marker - could identify who truly needs surveillance. Early data suggests it could reduce unnecessary procedures by 30%.

The goal? Reduce esophageal cancer deaths by 45% by 2035. That’s possible - but only if we get better at finding the right people, treating them at the right time, and making sure they get follow-up care.

What Should You Do If You Have Barrett’s Esophagus?

If you’ve been diagnosed with Barrett’s esophagus:

- Don’t panic. Most won’t get cancer.

- Get a second opinion on your biopsy. Especially if it says low-grade dysplasia.

- If you have confirmed dysplasia - treat it. Ablation cuts cancer risk by 90% compared to just watching.

- Take your PPIs as prescribed. Don’t skip doses.

- Quit smoking. It’s one of the biggest modifiable risks.

- Ask about surveillance intervals. Don’t wait until you feel worse.

If you’ve never been diagnosed but have chronic GERD - especially if you’re a man over 50 - talk to your doctor about an endoscopy. Early detection saves lives.

Can Barrett’s esophagus go away on its own?

Rarely. While the abnormal tissue may shrink with strong acid suppression, it almost never disappears completely without treatment. The risk of cancer remains as long as the metaplastic tissue is present. That’s why surveillance or ablation is recommended for those with dysplasia.

Is ablation painful?

The procedure itself is done under sedation, so you won’t feel it. Afterward, most people have mild chest discomfort or sore throat for a few days. Strictures - narrowing of the esophagus - can cause pain during swallowing and require dilation, which can be uncomfortable. About one in three patients need at least one dilation after RFA.

Do I still need endoscopies after ablation?

Yes. Even after complete eradication, Barrett’s can return. Guidelines recommend follow-up endoscopies every 1-3 years, depending on your history. You’ll also need biopsies to check for recurrence. Stopping surveillance is one of the biggest mistakes patients make.

Can I drink alcohol if I have Barrett’s esophagus?

Yes, alcohol doesn’t increase your risk of progression to cancer. But it can worsen reflux symptoms. If alcohol triggers your heartburn, avoiding it will help control your reflux - and that’s what matters most for preventing further damage.

Is cryoablation better than RFA?

It depends. RFA is more effective at erasing the abnormal tissue completely. Cryoablation is safer if you’ve had prior strictures or are at high risk for them. It’s also less painful after treatment. Many centers now use cryoablation as a second-line option or for patients who can’t tolerate RFA.

How do I know if I’m a candidate for ablation?

You’re a candidate if you have confirmed low-grade or high-grade dysplasia on biopsy, reviewed by an expert GI pathologist. If you have no dysplasia, ablation is not recommended - surveillance is enough. The key is accurate diagnosis. Don’t proceed with treatment unless dysplasia is confirmed.

Final Thought: It’s About Prevention, Not Panic

Barrett’s esophagus is a warning, not a death sentence. With the right care - accurate diagnosis, timely ablation, and lifelong management - the chance of dying from esophageal cancer drops dramatically. The tools are here. The science is solid. What’s missing is awareness. If you’ve had heartburn for years, don’t wait for pain to become cancer. Talk to your doctor. Get checked. Take control.

Shae Chapman

January 1, 2026 AT 06:38OMG I just found out I have Barrett’s and I was like… is this it?? 😭 But then I read this and felt so much better. Ablation sounds scary but way better than losing my esophagus 🙏 I’m scheduling my endo next week. Also, I quit coffee. No more 10pm espresso. 🤞

Nadia Spira

January 1, 2026 AT 18:23Let’s be real - this is just Big Gastro’s profit machine disguised as preventive medicine. RFA? Cryoablation? You’re paying $12K to have your esophagus zapped because someone decided metaplasia = ‘precancer’ instead of ‘adaptive response.’ The real epidemic? Overdiagnosis. And you’re all drinking the PPI Kool-Aid like it’s gospel. Pathologists can’t even agree on LGD - how are you trusting this? 🤡

henry mateo

January 1, 2026 AT 23:13Hey i just got diagnosed with lgd last month and i was so scared. i read this whole thing and it actually helped a lot. i didnt know about the pathologist second opinion thing - gonna get that done. also i quit smoking last week so fingers crossed. thanks for writing this. you saved me from a panic spiral. 🙏

Kunal Karakoti

January 2, 2026 AT 23:20The human body is an intricate system of adaptation. Barrett’s metaplasia is not a flaw - it is a survival strategy. Our medical paradigm, however, seeks to eliminate variation rather than understand it. Ablation may reduce statistical risk, but does it restore harmony? Or merely impose control? The real question is not whether we can remove the tissue - but whether we should disrupt the body’s attempt to cope. Perhaps the answer lies not in heat or cold, but in silence - in letting the body breathe without pharmaceutical intervention.

Kelly Gerrard

January 3, 2026 AT 13:13Stop wasting time with anecdotal stories. The data is clear: ablation reduces cancer risk by 90%. If you have dysplasia and you’re not treating it you’re being irresponsible. Your lifestyle choices matter. Quit smoking. Take your PPI. Get monitored. No excuses. This isn’t optional. It’s survival. #TakeControl

Cheyenne Sims

January 4, 2026 AT 23:56As an American woman who lost her father to esophageal cancer, I can tell you this: if your doctor says you have Barrett’s with dysplasia and you don’t get ablation, you’re gambling with your life. This isn’t some fringe theory - it’s standard of care. The fact that rural communities don’t have access is a national disgrace. We need policy change, not passive philosophy. Get treated. Get informed. Don’t wait until it’s too late.

Glendon Cone

January 5, 2026 AT 16:38Just had my first RFA last month - 3 sessions so far. The dilation after? Brutal. Felt like swallowing glass. But the chest pain? Gone. I used to wake up at 3am with burning throat - now I sleep like a baby. Also, I started walking after dinner. 20 mins. No more pizza at midnight. Small changes, big difference. If you’re scared - I was too. But this worked for me. 💪

Aayush Khandelwal

January 6, 2026 AT 16:31Let’s not romanticize ablation like it’s a magic wand. The real issue is upstream: our food system, our stress culture, our sleep deprivation. We treat the tissue, not the terrain. RFA clears metaplasia - but if you’re still eating ultra-processed meals, chugging soda, and sleeping 5 hours a night, the tissue will return. The procedure is brilliant, but it’s a Band-Aid on a hemorrhage. We need systemic change, not just endoscopic fireworks.

Sandeep Mishra

January 7, 2026 AT 09:03Hey everyone - I’m a GI nurse in Delhi and I’ve seen patients from rural India fly to Mumbai just for ablation. They sell livestock, borrow money. No insurance. No follow-up. I’ve watched people get RFA and then vanish because they can’t afford the next endoscopy. This isn’t just a medical issue - it’s a justice issue. We need global access. Not just for Americans with good insurance. For the farmer in Bihar, the factory worker in Jakarta, the single mom in Mexico City. Your life isn’t a privilege. It’s a right. 🌍❤️