Most people know about LDL cholesterol - the so-called "bad" cholesterol - and how it clogs arteries. But there’s another cholesterol particle hiding in plain sight, one that doesn’t show up on routine blood tests and isn’t touched by diet or exercise. It’s called lipoprotein(a), or Lp(a). And if you have high levels, you could be at serious risk for a heart attack or stroke - even if your other cholesterol numbers look perfect.

What Exactly Is Lipoprotein(a)?

Lipoprotein(a), or Lp(a), is a type of lipoprotein that carries cholesterol and fat through your bloodstream. It looks a lot like LDL cholesterol, but with one critical difference: it has an extra protein attached - apolipoprotein(a). This protein makes Lp(a) sticky. It latches onto damaged areas in your artery walls, pulls in more cholesterol, and helps form plaques. It also interferes with your body’s ability to break down blood clots, which can trigger heart attacks and strokes.

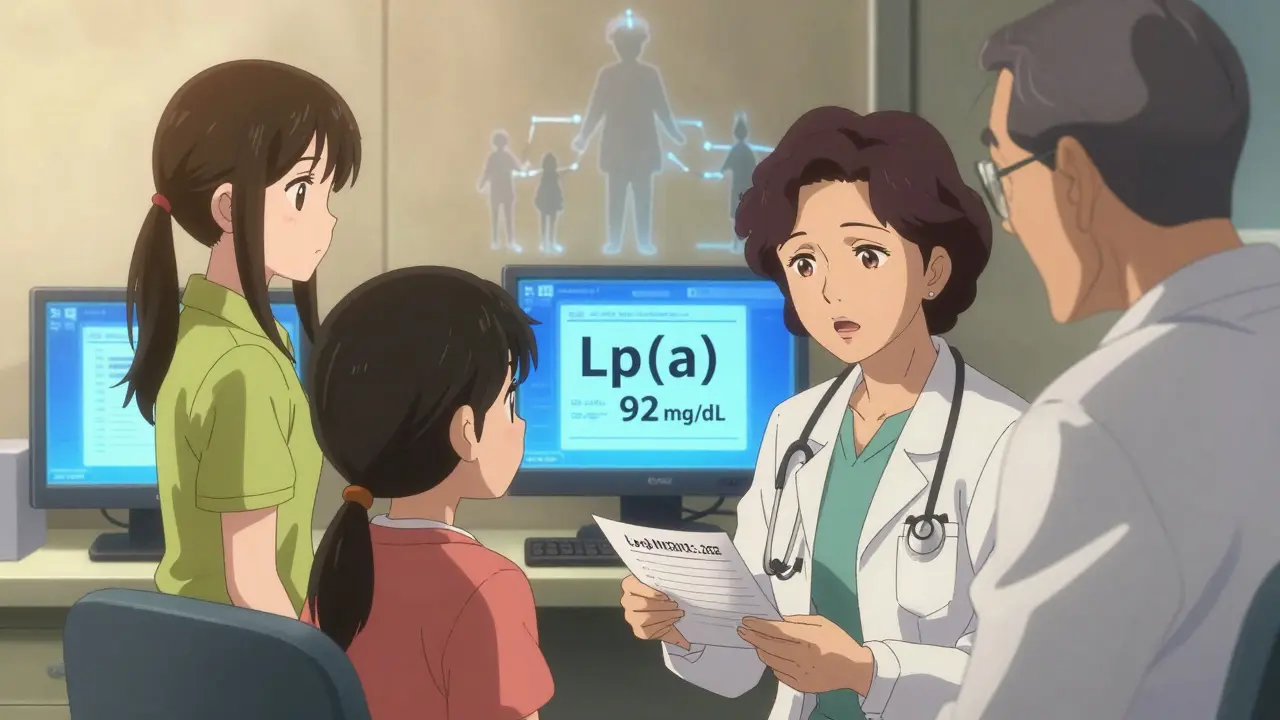

Unlike regular cholesterol, Lp(a) isn’t something you can control with salads or gym sessions. Your levels are mostly set by your genes - about 90% of the variation comes from your DNA. That means if your parent had high Lp(a), you have a 50% chance of inheriting it. And if you do, you’re likely carrying this risk for life.

Why Most Doctors Miss It

Here’s the frustrating part: Lp(a) isn’t part of a standard lipid panel. Unless your doctor specifically orders it, you won’t know your levels. That’s why it’s called a "hidden" risk. Many people with heart disease have no obvious risk factors - no smoking, no diabetes, no obesity - but their Lp(a) is sky-high. In fact, about one in five people globally have elevated levels, making it the most common inherited cause of early heart disease.

Cardiologists like Dr. Gregory Schwartz at the University of Colorado say it’s time to change that. Major organizations, including the American Heart Association and the American College of Cardiology, now recommend testing Lp(a) at least once in every adult’s lifetime. It’s especially important if you have:

- A family history of early heart disease (before age 55 in men, before 65 in women)

- A personal history of heart attack or stroke without clear causes

- Familial hypercholesterolemia

- Aortic valve stenosis

Even if you don’t have any of these, getting tested is worth considering. It’s a simple blood draw - no fasting needed. The test measures Lp(a) in either milligrams per deciliter (mg/dL) or nanomoles per liter (nmol/L). The cutoff for high risk is generally above 50 mg/dL (or 125 nmol/L). Levels above 90 mg/dL (190 nmol/L) are considered very high, putting you at risk equal to someone with inherited high cholesterol.

Who’s Most at Risk?

Not everyone has the same Lp(a) levels. Genetics play a huge role, but so does ancestry. People of African descent tend to have significantly higher levels than those of European, Asian, or Hispanic backgrounds. Studies show Black individuals are more likely to have levels that put them at high risk.

Gender matters too. Women often see their Lp(a) levels rise after menopause. That’s because estrogen helps keep Lp(a) in check. When estrogen drops, so does that protection. This may explain why heart disease risk spikes in women after 50 - even if they’ve eaten well and stayed active.

But here’s the key point: no matter your race or gender, higher Lp(a) means higher risk. There’s no "safe" level - the higher the number, the greater the danger to your heart and arteries.

How Lp(a) Damages Your Heart

Lp(a) doesn’t just add to plaque - it makes it worse. Its structure includes special parts called kringle domains that act like molecular glue. These domains:

- Bind to damaged areas in artery walls

- Attract inflammatory cells that destabilize plaques

- Block your body’s natural clot-busting system (fibrinolysis)

This triple threat means Lp(a) doesn’t just cause blockages - it makes them more likely to rupture. And when a plaque ruptures, a clot forms. That’s when you get a heart attack or stroke.

Lp(a) also plays a role in aortic valve stenosis - a condition where the heart’s main valve narrows. The same sticky particles that build plaque in arteries also build up on the valve, causing it to stiffen and fail. This isn’t just about cholesterol. It’s about genetics driving structural damage over decades.

What Doesn’t Work - And Why

If you’ve been told to eat less saturated fat or take statins to lower your cholesterol, you might be surprised to learn that these won’t help much with Lp(a). Statins - the most common cholesterol drugs - barely move the needle. In fact, they can sometimes raise Lp(a) slightly.

Niacin (vitamin B3) can lower Lp(a) by 20-30%, but it comes with serious side effects: flushing, liver damage, and increased blood sugar. For most people, the risks outweigh the uncertain benefits.

Even lifestyle changes - diet, exercise, weight loss - have little to no effect on Lp(a) levels. This is why so many people are confused. They do everything "right," yet still end up with heart disease. The reason? They’re fighting a genetic battle with the wrong weapons.

What’s on the Horizon - Real Hope for the Future

There’s good news on the horizon. For the first time, drugs are being developed that target Lp(a) directly. The most promising are antisense oligonucleotides (ASOs), like pelacarsen. In early trials, pelacarsen lowered Lp(a) by up to 80% - a dramatic drop.

The big phase 3 trial, called Lp(a) HORIZON, is now underway. It’s tracking thousands of patients with very high Lp(a) levels and existing heart disease. The goal? To see if lowering Lp(a) actually prevents heart attacks, strokes, or death. Results are expected in 2025. If the trial succeeds, pelacarsen could become the first approved treatment specifically for high Lp(a).

Other drugs, like small interfering RNA (siRNA) therapies, are also in development. These work similarly to ASOs but may require less frequent dosing. The field is moving fast. Within the next few years, we may have targeted therapies that let people with high Lp(a) finally take control of their risk.

What You Can Do Today

While we wait for new drugs, you can still protect yourself. Even if Lp(a) is out of your control, you can lower your overall risk by managing the other factors:

- Keep your LDL low. If you have high Lp(a), your LDL should be under 70 mg/dL - even lower if you’ve had a heart event.

- Don’t smoke. Smoking damages arteries and makes Lp(a) more dangerous.

- Control blood pressure. High pressure stresses artery walls, giving Lp(a) more places to stick.

- Manage diabetes. High blood sugar speeds up plaque buildup.

- Stay active. Exercise doesn’t lower Lp(a), but it improves circulation, reduces inflammation, and helps control other risks.

Also, talk to your family. If you’re diagnosed with high Lp(a), encourage your siblings and children to get tested. It’s inherited - and early detection saves lives.

Final Thoughts: Knowledge Is Power

Lp(a) isn’t your fault. You didn’t cause it. You can’t fix it with diet or willpower. But you can know about it - and act on it. Getting tested is the first step. Knowing your level gives you clarity. It lets you work with your doctor to build a plan that’s tailored to your real risk.

For too long, Lp(a) has been ignored. But the science is clear: it’s a major, underdiagnosed threat. And now, with new treatments on the way, we’re entering a new era. The goal isn’t just to treat cholesterol - it’s to treat the hidden genetic risks that make heart disease strike so unexpectedly.

If you’ve had unexplained heart problems, or if heart disease runs in your family, ask your doctor for an Lp(a) test. It’s one blood draw. It could change everything.

Is lipoprotein(a) the same as LDL cholesterol?

No. While Lp(a) contains an LDL-like particle, it has an extra protein called apolipoprotein(a) attached. This makes it more likely to stick to artery walls, trigger inflammation, and block clot breakdown - making it more dangerous than regular LDL. Standard cholesterol tests don’t measure Lp(a), so you need a separate test.

Can I lower my Lp(a) with diet or exercise?

No. Unlike LDL or triglycerides, Lp(a) levels are not meaningfully affected by diet, exercise, weight loss, or most lifestyle changes. About 90% of your Lp(a) level is determined by your genes. While healthy habits won’t lower Lp(a), they’re still critical to reduce your overall heart disease risk.

Should everyone get tested for Lp(a)?

Major heart organizations now recommend testing at least once in adulthood - especially if you have a family history of early heart disease, a personal history of heart attack or stroke without clear causes, or familial hypercholesterolemia. But even if you don’t have these risk factors, testing can provide valuable insight into your long-term risk.

What’s considered a high Lp(a) level?

Levels above 50 mg/dL (or 125 nmol/L) are considered elevated and linked to increased cardiovascular risk. Levels above 90 mg/dL (190 nmol/L) are classified as very high and carry a risk similar to familial hypercholesterolemia. There’s no "safe" level - the higher the number, the greater the risk.

Are there any drugs available to treat high Lp(a)?

Currently, no drugs are approved specifically to lower Lp(a). Statins and niacin have limited or no effect and come with side effects. The most promising treatment, pelacarsen, is an antisense oligonucleotide that reduces Lp(a) by up to 80% in trials. Results from the phase 3 Lp(a) HORIZON trial are expected in 2025 - this could lead to the first approved therapy for high Lp(a).

If I have high Lp(a), will I definitely have a heart attack?

No. High Lp(a) increases your risk, but it doesn’t guarantee an event. Many people with elevated levels never have a heart attack. The key is knowing your level so you can aggressively manage all other risk factors - like LDL, blood pressure, and smoking - to offset the genetic risk.

Cam Jane

January 5, 2026 AT 21:18I got tested for Lp(a) last year after my dad had a stroke at 52. Turned out mine was 112 mg/dL. I was devastated at first - like, I eat clean, run 5Ks, no smoking - but then I realized this isn’t my fault. Knowledge is power. Now I keep my LDL under 60, take a low-dose aspirin, and push my doc to monitor my valve. You can’t change your genes, but you can outsmart them.

Dana Termini

January 6, 2026 AT 04:35This is one of the clearest explanations I’ve read on Lp(a). Finally, someone gets it - it’s not about willpower. It’s biology. And it’s not rare. It’s just invisible.

Susan Arlene

January 7, 2026 AT 05:14so like... my mom had a heart attack at 58 and no one ever tested her for this? like... what even is the medical system

Mukesh Pareek

January 8, 2026 AT 20:41It is imperative to underscore that Lp(a) is a prothrombotic, proinflammatory, atherogenic lipoprotein particle, genetically determined, and refractory to conventional lipid-modifying interventions. The absence of standardized assay methodologies across laboratories further complicates clinical interpretation. One must advocate for mass spectrometry-based quantification for precision.

Matt Beck

January 9, 2026 AT 02:59It’s wild 🤯 how our bodies are just… programmed. Like, we’re not broken. We’re just born with a glitch in the code. And now science is finally catching up. I feel like we’re on the edge of a medical revolution. 🌱🫶

Kelly Beck

January 10, 2026 AT 11:03If you’re reading this and you’ve had unexplained heart issues - please, please, please ask your doctor for the Lp(a) test. It’s one blood draw. One moment. It could save your life, or your child’s life. You don’t need to suffer in silence. There’s a name for this now. And we’re not alone. 💪❤️

Beth Templeton

January 11, 2026 AT 22:57Statins raise Lp(a)? Wow. So the whole cholesterol myth was built on sand and pharma ads.

Indra Triawan

January 13, 2026 AT 05:31I wonder if this is why my sister’s heart failed at 41. She ate kale, did yoga, drank green juice… I just wish someone had told us this was genetic. Now I’m scared to have kids.

Melanie Clark

January 14, 2026 AT 03:25Big Pharma doesn't want you to know this because they make billions off statins. The real cure is already here - it's called fasting and cold exposure - but they suppress it. Lp(a) is just a distraction. The system is rigged. You're being played.

Venkataramanan Viswanathan

January 16, 2026 AT 03:00In India, we see this often - young people with heart attacks, no diabetes, no obesity. My cousin, 34, had a massive MI. We tested him. Lp(a) was 140. His father had the same. This is not a Western problem. It’s a human problem.

Vinayak Naik

January 16, 2026 AT 12:19yo i got my lpa tested after my uncle keeled over at 47 - 89 mg/dl. doc said 'eh, keep chillin' - but i started taking omega-3s and walking 10k steps daily. my ldl dropped like a rock. not sure if it helped lpa but at least i ain't feelin' helpless

Kiran Plaha

January 16, 2026 AT 20:16What’s the cost of the test? Is it covered by insurance here?

Amy Le

January 18, 2026 AT 19:56Why are we even talking about this? America’s health system is a joke. If you’re not rich, you’re just a statistic. Lp(a) doesn’t care about your DNA - it cares about your wallet.