When a generic drug company wants to bring a new product to market, they don’t need to run full clinical trials like the original brand did. Instead, they prove bioequivalence - that their version delivers the same amount of drug into the bloodstream at the same rate as the brand-name version. But proving this isn’t just about running a few tests. It’s about getting the statistics right. And if you get the sample size wrong, your entire study can fail - no matter how good the drug is.

Why Sample Size Matters in Bioequivalence Studies

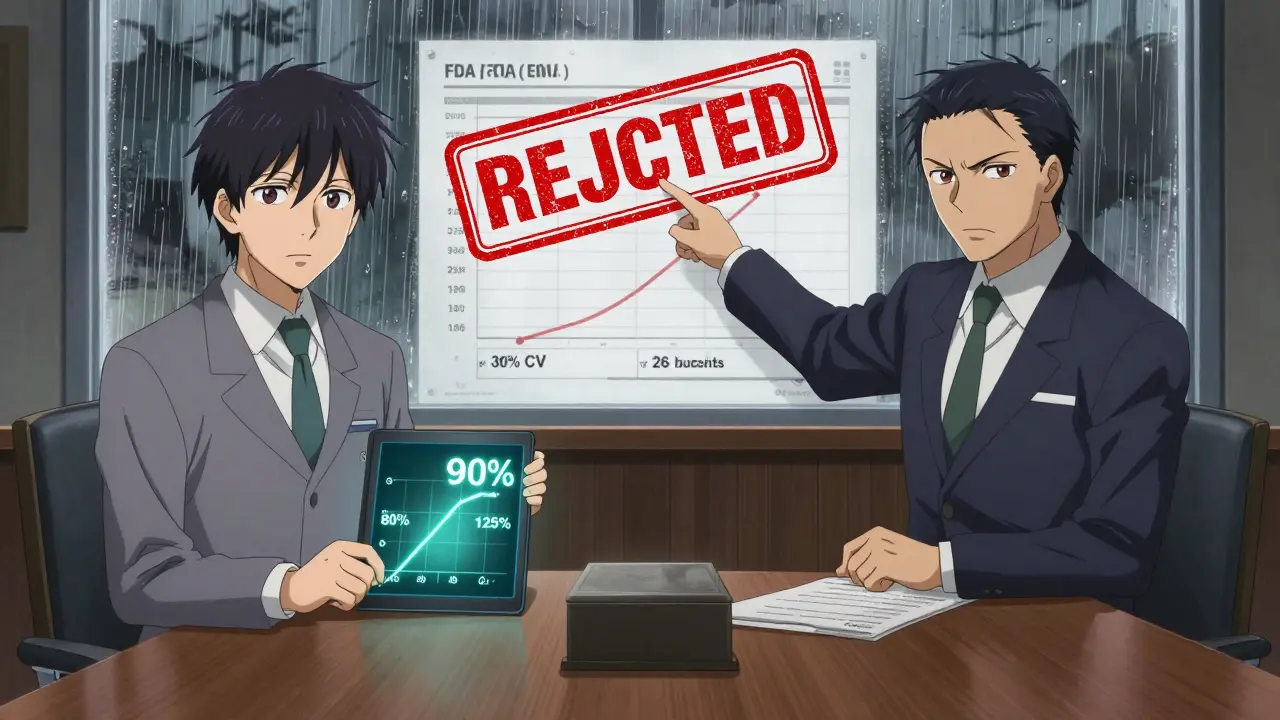

Bioequivalence (BE) studies compare how your body absorbs a test drug versus a reference drug. The goal isn’t to show one is better - it’s to show they’re the same within strict limits. Regulators like the FDA and EMA require that the 90% confidence interval for the ratio of test to reference drug (usually measured by Cmax and AUC) falls entirely between 80% and 125%. If it doesn’t, the drug isn’t approved.

But here’s the catch: even if two drugs are truly equivalent, a small study might not detect it. That’s called a Type II error - you miss a real effect. On the flip side, if you enroll too many people, you waste money, time, and expose more volunteers to unnecessary procedures. Both are costly mistakes.

Studies with underpowered designs are one of the top reasons generic drug applications get rejected. In 2021, the FDA found that 22% of Complete Response Letters cited inadequate sample size or power calculations. That’s not a small number. It means nearly one in five submissions failed because the math didn’t add up.

What Determines How Many People You Need?

Sample size isn’t pulled out of thin air. It’s calculated using four key inputs:

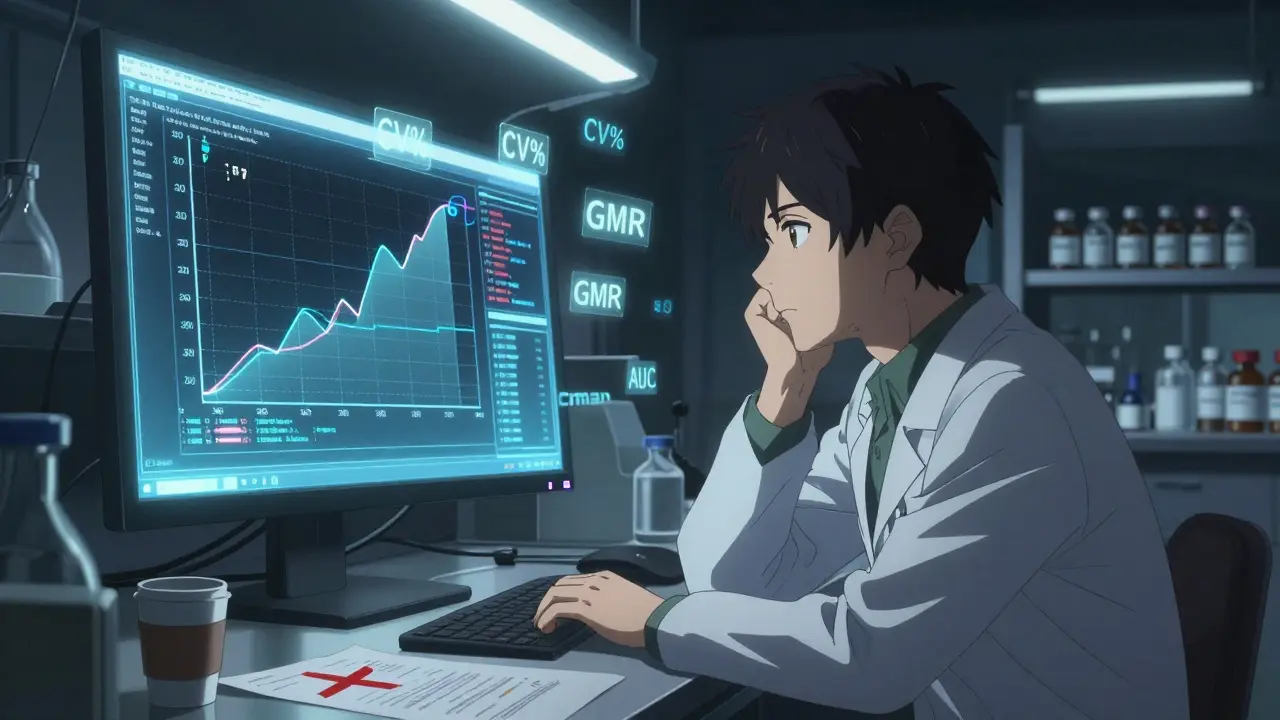

- Within-subject coefficient of variation (CV%) - how much a person’s own response varies from one dosing period to another. For most drugs, this ranges from 10% to 35%. But for highly variable drugs (like warfarin or clopidogrel), CV can exceed 40%.

- Expected geometric mean ratio (GMR) - how close you think the test drug’s absorption is to the reference. Most assume 0.95-1.05, meaning the test delivers 95% to 105% of the reference’s effect.

- Target power - the chance your study will correctly detect equivalence if it’s true. 80% is the minimum accepted by regulators. 90% is often expected, especially for narrow therapeutic index drugs (like lithium or digoxin).

- Equivalence margins - typically 80-125%, but can widen for highly variable drugs under special rules like RSABE.

Let’s say you’re testing a drug with a 20% CV, expect a GMR of 0.95, want 80% power, and use the standard 80-125% range. You’ll need about 26 subjects. Now increase the CV to 30%. Suddenly, you need 52 subjects. Double the variability - double the people.

And if the CV hits 40%? Without special allowances, you might need over 100 people. That’s expensive. That’s why regulators created RSABE - Reference-Scaled Average Bioequivalence. For drugs with CV > 30%, RSABE lets you widen the equivalence range based on how variable the drug is. This can cut your sample size in half. A study that would’ve needed 120 subjects under standard rules might only need 48 with RSABE.

How Power Calculations Actually Work

The math behind sample size isn’t simple. Pharmacokinetic data (like Cmax and AUC) don’t follow a normal distribution - they’re log-normal. So calculations happen on the log scale. The formula looks like this:

N = 2 × (σ² × (Z₁₋α + Z₁₋β)²) / (ln(θ₁) - ln(μₜ/μᵣ))²

That’s intimidating. But you don’t need to memorize it. What you do need to know is what each piece means:

- σ² = within-subject variance (derived from CV%)

- Z₁₋α and Z₁₋β = statistical constants for alpha (0.05) and power (0.80 or 0.90)

- θ₁ = lower equivalence limit (0.80)

- μₜ/μᵣ = expected test/reference ratio (e.g., 0.95)

Most researchers use software like PASS, nQuery, or FARTSSIE. These tools handle the complexity. But here’s the problem: if you plug in the wrong numbers, you get the wrong answer.

Many teams use literature values for CV - but the FDA found that literature-based CVs underestimate true variability by 5-8 percentage points in 63% of cases. That’s a big gap. If you assume a 20% CV based on old papers, but the real CV is 28%, your study is underpowered before it even starts.

Best practice? Use pilot data. Even a small pilot study with 12-16 subjects gives you a much more realistic estimate. Dr. Laszlo Endrenyi’s research showed that using optimistic CV estimates caused 37% of BE study failures in oncology generics between 2015 and 2020.

What Most People Get Wrong

Even experienced teams make the same mistakes over and over:

- Ignoring dropout rates - If you calculate 26 subjects and expect 10% to drop out, you need to enroll 30. Otherwise, your final power drops below 80%.

- Only checking one endpoint - You must have enough power for both Cmax and AUC. If you only power for AUC, your Cmax result might fail. Only 45% of sponsors do joint power calculations.

- Assuming perfect GMR - Assuming a ratio of exactly 1.00 is dangerous. If the real ratio is 0.95, your sample size needs to increase by 32% to maintain power.

- Not documenting everything - The FDA’s 2022 review template requires full documentation: software used, version, inputs, justification, dropout adjustment. Missing this caused 18% of statistical deficiencies in 2021.

Another hidden trap: sequence effects in crossover designs. If the order of dosing (test first or reference first) affects results, your analysis must account for it. In 2022, 29% of EMA rejections cited improper handling of sequence effects.

Regulatory Differences Between FDA and EMA

Don’t assume global rules are the same. The FDA and EMA have subtle but critical differences:

- Power level - FDA often expects 90% power for narrow therapeutic index drugs. EMA accepts 80%.

- Equivalence margins - EMA allows 75-133% for Cmax in some cases, which can reduce sample size by 15-20% compared to the standard 80-125% range.

- RSABE rules - Both accept it for CV > 30%, but EMA’s formula for widening margins is slightly different.

For global submissions, you have to design for the strictest requirement. If you’re targeting both markets, plan for 90% power and 80-125% margins. That way, you won’t get rejected in one region because you optimized for the other.

Tools You Should Use

You don’t need to code your own calculator. But you do need to pick the right tool:

- Pass 15 - Most comprehensive, fully aligned with FDA and EMA guidelines. Used by 70% of industry statisticians.

- ClinCalc Sample Size Calculator - Free, web-based, easy to use. Great for quick estimates. Shows real-time graphs as you adjust inputs.

- FARTSSIE - Free, open-source, designed specifically for BE studies. Good for academic use.

- nQuery - Commercial, widely used in large pharma. Strong documentation and support.

Pro tip: Always run multiple scenarios. What happens if CV is 25% instead of 20%? What if GMR is 0.92? Use the tool to build a range - not just one number. That’s what regulators want to see: you thought through uncertainty.

The Future: Model-Informed Bioequivalence

Traditional methods rely on population averages. But new approaches use modeling - simulating how each individual responds based on genetics, metabolism, or other factors. This is called model-informed bioequivalence.

The FDA’s 2022 Strategic Plan supports this shift. Early results show it can reduce sample sizes by 30-50% for complex products like inhalers or injectables. But it’s still rare - only 5% of submissions use it in 2023. Why? Regulatory uncertainty. It’s hard to get approval without precedent.

Still, it’s coming. The next generation of BE studies will be smarter, not bigger. But for now, the old rules still apply. And if you don’t follow them, your drug won’t get approved.

What You Should Do Today

If you’re planning a BE study, here’s your checklist:

- Run a small pilot study to get real CV% - don’t rely on literature.

- Use a validated tool (PASS, ClinCalc) to calculate sample size for both Cmax and AUC.

- Adjust for 10-15% dropout rate.

- Document every assumption: software, version, inputs, justification.

- If CV > 30%, explore RSABE - it could save you dozens of subjects.

- Plan for 90% power if targeting both FDA and EMA.

There’s no magic number. But there is a right way. And if you skip the math, you’re gambling with millions of dollars and months of work. In bioequivalence, statistics aren’t optional. They’re the foundation.

What is the minimum acceptable power for a bioequivalence study?

The minimum acceptable power is 80%, as defined by both the FDA and EMA. However, many regulators, especially the FDA, expect 90% power for drugs with a narrow therapeutic index (like warfarin or digoxin). Studies with only 80% power have a 1 in 5 chance of failing even if the drugs are truly equivalent. For regulatory submissions, aiming for 90% power is the safest approach.

How does within-subject variability (CV%) affect sample size?

Within-subject CV% is the biggest driver of sample size. For example, with a 20% CV and 80% power, you might need only 26 subjects. But if the CV increases to 30%, you need 52. At 40% CV, you could need over 100 - unless you qualify for RSABE. High variability means more uncertainty in measurements, so you need more people to detect true equivalence.

Can I use literature values for CV% in my sample size calculation?

It’s risky. The FDA found that literature-based CV% estimates underestimate true variability by 5-8 percentage points in 63% of cases. This leads to underpowered studies. Best practice is to use data from your own pilot study. Even a small pilot with 12-16 subjects gives you a much more accurate estimate than published papers.

What is RSABE and when should I use it?

RSABE stands for Reference-Scaled Average Bioequivalence. It’s a method used for highly variable drugs (CV > 30%) where standard 80-125% limits become impractical. RSABE widens the equivalence range based on the drug’s actual variability, reducing the required sample size. For example, instead of needing 120 subjects, you might only need 48. Both the FDA and EMA allow RSABE, but you must justify your CV estimate and follow their specific formulas.

Do I need to power for both Cmax and AUC?

Yes. Regulatory agencies require bioequivalence for both Cmax (peak concentration) and AUC (total exposure). If you only calculate power for one, your study may pass one endpoint but fail the other. Only 45% of sponsors currently do joint power calculations. Skipping this step is a common reason for study failure.

What happens if I don’t account for dropouts in my sample size?

If you enroll exactly the number calculated by your power analysis and some participants drop out, your final sample size falls below the target. This reduces your statistical power - sometimes below 80%. Industry best practice is to increase your enrollment by 10-15% to compensate for expected dropouts. For example, if you need 26 subjects, enroll 30.

Michael Burgess

January 4, 2026 AT 14:26Man, I’ve seen so many teams skip the pilot study and just grab CV numbers from some 2018 paper. Then they’re shocked when their study gets rejected. Real talk? If you’re not running at least 12 subjects to get your own variability data, you’re just gambling with FDA’s patience. And that’s not just expensive-it’s disrespectful to the volunteers who show up.

Tiffany Channell

January 6, 2026 AT 02:02Of course they reject 22% of submissions-because most of these companies treat stats like a suggestion, not a law. You don’t get to wing it with life-saving drugs. If you can’t do the math, don’t submit. Simple.

veronica guillen giles

January 7, 2026 AT 04:55Ohhh so THAT’S why my cousin’s generic blood pressure med gives her migraines? Maybe it’s not the drug… maybe it’s the ‘20% CV’ they pulled out of their butt. 😒

Hank Pannell

January 9, 2026 AT 02:55The real issue isn’t just sample size-it’s epistemic humility. We treat pharmacokinetic models as if they’re Newtonian physics, but biological systems are chaotic, nonlinear, and context-dependent. The 80-125% range is a statistical fiction-useful, yes, but not ontologically true. We’re quantifying the unquantifiable, and pretending it’s precision. That’s not science. It’s ritualized approximation.

And yet, we build billion-dollar regulatory frameworks on this. The irony? The more we refine the math, the more we obscure the biological truth. Maybe we need less software, more phenomenology.

RSABE is a band-aid on a bullet wound. It doesn’t solve the core problem: we don’t understand inter-individual variability well enough to model it reliably. We’re just making the numbers look prettier.

And don’t get me started on the ‘90% power’ dogma. Why 90? Why not 87? Why not 93? It’s arbitrary. We’ve turned statistical convention into moral imperative. That’s not evidence-based-it’s bureaucratic theology.

Meanwhile, the real innovation-model-informed BE-is sidelined because regulators fear the unknown. We’re optimizing for compliance, not discovery. And that’s the tragedy.

Angela Goree

January 10, 2026 AT 10:47Foreign companies think they can just copy-paste their stats and ship it to the U.S.? No. We have standards. Real ones. Not the ‘oh, it’s fine in India’ nonsense. If you can’t meet FDA math, go sell your product somewhere else.

Kerry Howarth

January 11, 2026 AT 05:09Always adjust for dropouts. Always. 10-15% is conservative. I’ve seen 20%+ in real studies. Never trust the ideal case.

Brittany Wallace

January 13, 2026 AT 01:50It’s wild how we treat statistics like magic spells-plug in numbers, say the right words, and poof! Approval. But real science? It’s messy. It’s humans with fluctuating metabolisms, sleep schedules, coffee intake, and stress levels. No software can capture that. We need more empathy in the math, not just more precision.

Also, shoutout to the volunteers. They’re not numbers. They’re people who show up for a 12-hour fast, multiple blood draws, and a room with no windows. We owe them better than lazy CV estimates.

And yeah, I used emoticons once. But I meant it. 💙

JUNE OHM

January 13, 2026 AT 09:06Wait… so you’re telling me the FDA doesn’t want us to use AI to predict how people metabolize drugs? That’s because they’re in bed with Big Pharma, obviously. They want you to enroll 100 people so they can charge more. It’s all a scam. 🤫

Shanahan Crowell

January 13, 2026 AT 21:54Just wanted to say-this post saved me. I was about to submit a study with literature CVs. Now I’m running a pilot. Thank you. Seriously. 🙏

Liam Tanner

January 14, 2026 AT 17:33One thing nobody talks about: sequence effects. I’ve seen so many studies ignore washout periods or assume no carryover. Then they get rejected for ‘inappropriate crossover design.’ It’s not rocket science-just pay attention.

Ian Ring

January 14, 2026 AT 20:20Pass 15 is the gold standard, yes-but have you tried the open-source FARTSSIE? It’s clunky, but it’s transparent. And for academic labs? No license fees. Just make sure you’re using version 2.1.3-2.1.4 has a bug in the RSABE module.

Neela Sharma

January 15, 2026 AT 12:06Bro, I work in Mumbai lab. We used to rely on old papers. Then we did pilot. CV jumped from 22% to 31%. We doubled sample size. Got approved. No drama. No tears. Just real data. 🙌

Philip Leth

January 16, 2026 AT 01:52RSABE is the real MVP for generics. I’ve seen a study go from 110 to 42 subjects just by switching. That’s like cutting the budget in half. Why isn’t everyone using it? Probably because someone’s still using Excel to calculate power. 😅

Shruti Badhwar

January 16, 2026 AT 14:54While it is commendable that the post emphasizes the importance of statistical rigor, it is imperative to acknowledge that regulatory harmonization remains a critical challenge. The divergence between FDA and EMA guidelines, particularly regarding power thresholds and equivalence margins, necessitates a strategic, risk-based approach to global submissions. Failure to align with the most stringent criterion is not merely suboptimal-it is commercially untenable.

Ian Detrick

January 16, 2026 AT 15:01Look-I get it. Stats are boring. But if your drug doesn’t pass bioequivalence, it doesn’t get made. And if it doesn’t get made, people who need it can’t afford it. So yeah, do the math. Not because the FDA says so. Because it’s the right thing to do.