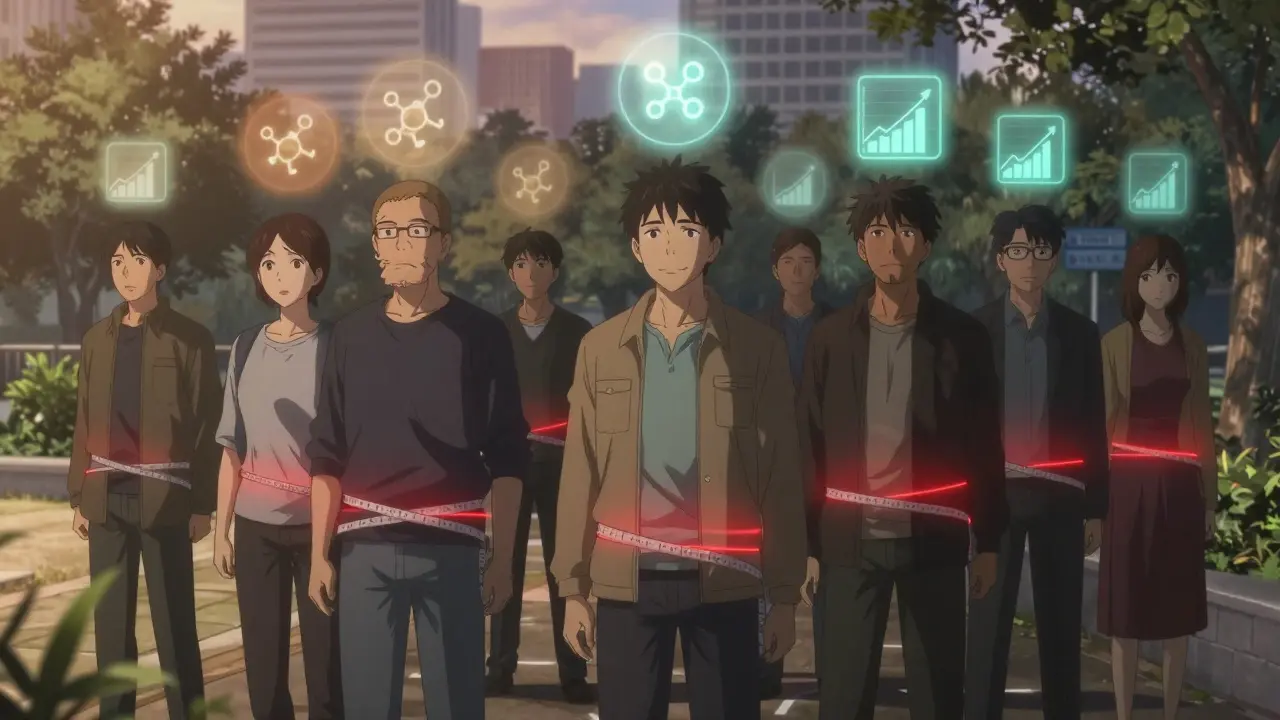

More than one in three adults in the U.S. has metabolic syndrome - and many don’t even know it. It doesn’t come with a rash, a cough, or a sharp pain. Instead, it hides in plain sight: a growing waistline, stubbornly high triglycerides, and fasting blood sugar that’s just a little too high. These aren’t isolated problems. They’re signals - early warnings - that your body’s metabolism is slipping out of balance. And if left unchecked, this trio of issues can set you on a path toward heart disease, stroke, and type 2 diabetes.

What Exactly Is Metabolic Syndrome?

Metabolic syndrome isn’t a single disease. It’s a cluster of conditions that happen together. To be diagnosed, you need at least three out of five specific markers: large waist size, high triglycerides, low HDL (the "good" cholesterol), high blood pressure, and elevated fasting glucose. The most important of these? Waist size. It’s not just about looking heavier - it’s about where the fat sits. Belly fat, especially the kind that wraps around your organs, is biologically active. It doesn’t just store energy; it sends out signals that disrupt how your body uses insulin.

Doctors first started grouping these risk factors together in the late 1990s. Since then, research has shown that people with metabolic syndrome are twice as likely to develop heart disease and five times more likely to get type 2 diabetes than those without it. The numbers don’t lie: by age 60, nearly half of American adults meet the criteria. And it’s not just a Western problem. In South Asia, people can develop metabolic syndrome at much smaller waist sizes - as low as 31.5 inches for women - because fat distribution and insulin sensitivity vary by ethnicity.

Why Waist Size Matters More Than You Think

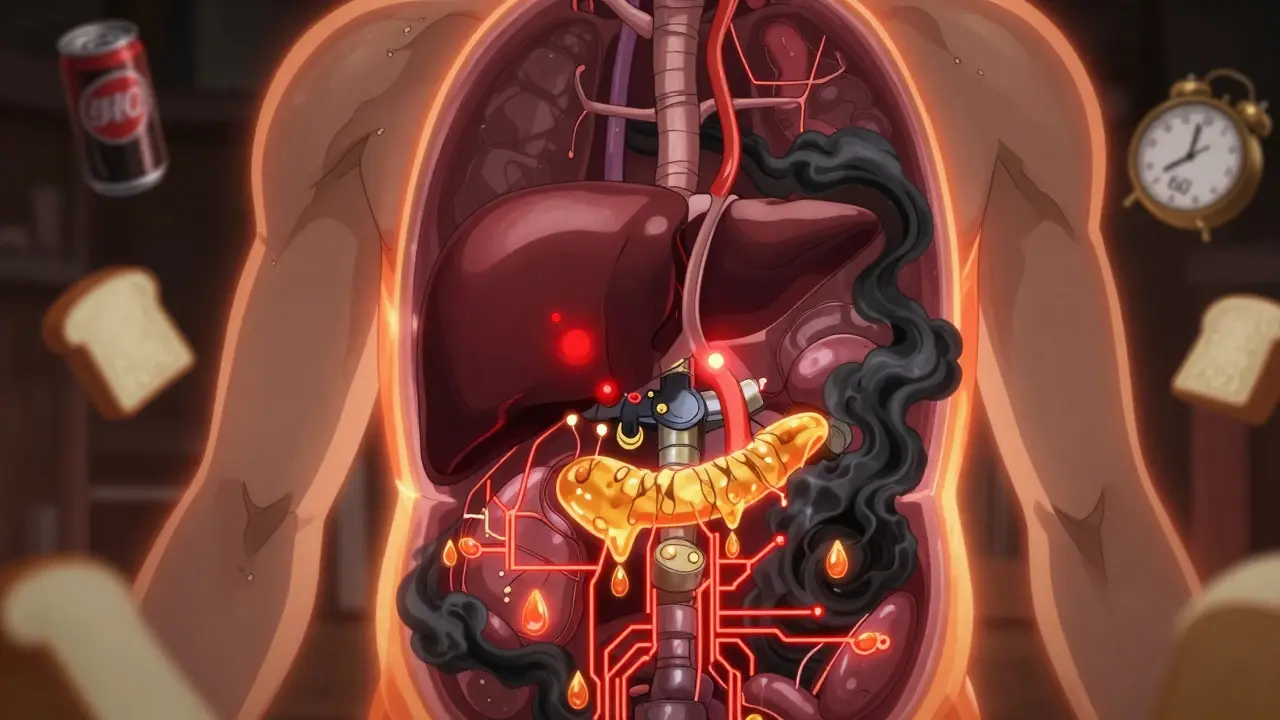

Measuring your waist isn’t about vanity. It’s a direct readout of visceral fat - the kind that clings to your liver, pancreas, and intestines. This fat isn’t passive. It releases inflammatory chemicals like tumor necrosis factor-alpha and resistin, which interfere with insulin’s ability to do its job. When insulin can’t signal cells to take in glucose, your blood sugar rises. Your pancreas responds by pumping out even more insulin, until eventually, it burns out.

The thresholds are clear: for men, a waist over 40 inches (102 cm) is a red flag. For women, it’s 35 inches (88 cm). But here’s the catch: if you’re of South Asian, Chinese, or Japanese descent, those numbers drop. For South Asian women, 31.5 inches (80 cm) is enough to raise risk. Why? Because their bodies store fat differently - more around organs, less under the skin. That’s why global health organizations now recommend ethnicity-specific cutoffs.

And the impact is real. Every extra 4 inches (10 cm) around your waist increases your risk of heart disease by 10%, even if your BMI is normal. You can be "skinny" and still have dangerous belly fat. That’s called TOFI - thin on the outside, fat inside. It’s common in people who eat processed foods, sit too much, and don’t move enough.

Triglycerides: The Silent Warning Sign

Triglycerides are the main type of fat in your blood. When you eat more calories than your body needs - especially from sugar and refined carbs - your liver turns the excess into triglycerides and sends them out for storage. High levels mean your liver is overworked, and your body is struggling to manage energy.

The diagnostic cutoff is 150 mg/dL. But here’s what most people don’t realize: once you hit 200 mg/dL, your risk for heart attack and stroke jumps significantly, even if your LDL (bad cholesterol) is fine. That’s because high triglycerides are linked to smaller, denser LDL particles - the kind that slip into artery walls more easily and cause plaque.

And here’s the connection to your waist: belly fat doesn’t just make triglycerides go up - it also makes them harder to clear. When insulin resistance sets in, your body stops breaking down triglycerides efficiently. That’s why someone with a large waist and high triglycerides is often the same person with prediabetes. It’s not coincidence. It’s cause and effect.

What raises triglycerides? Sugar - especially liquid sugar like soda and fruit juice. Alcohol. Refined grains like white bread and pasta. Trans fats. And a sedentary lifestyle. Cut those out, and triglycerides can drop 20-50% in just a few weeks.

Glucose Control: The Body’s Burning Fuse

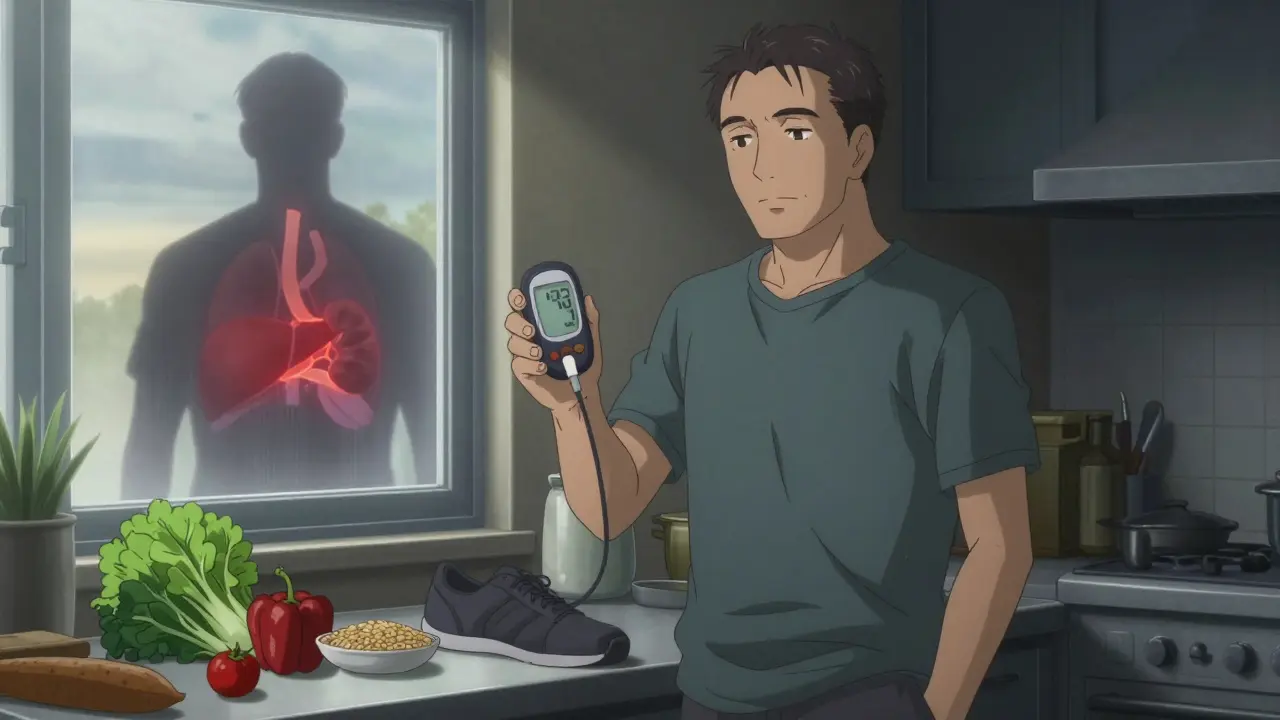

Fasting blood sugar of 100 mg/dL or higher means you’re in the prediabetes range. That’s not a diagnosis of diabetes - it’s a warning light. Your cells are starting to ignore insulin. Your liver is pumping out too much glucose. Your pancreas is working overtime.

The Diabetes Prevention Program, a landmark study followed for over 15 years, showed that people with prediabetes who lost just 5-7% of their body weight and walked 150 minutes a week reduced their chance of developing type 2 diabetes by 58%. That’s more effective than any medication. Metformin helped too - but only by 31%. Lifestyle changes beat pills every time.

And here’s the feedback loop: high glucose worsens insulin resistance. High insulin drives fat storage, especially in the belly. Fat releases more inflammation. Inflammation makes insulin less effective. It’s a cycle - and it spins faster the longer you ignore it.

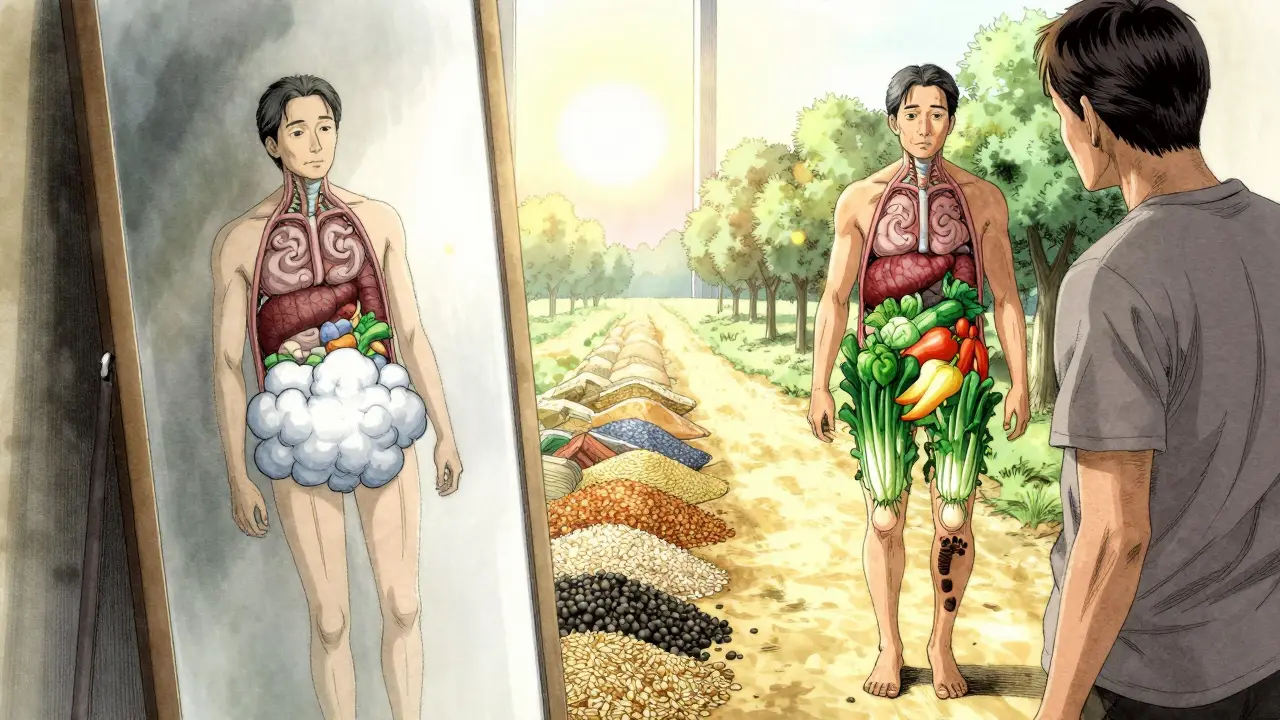

What helps? Fiber. Whole foods. Less sugar. Eating protein and fat with carbs slows glucose spikes. Walking after meals helps your muscles soak up glucose before it turns to fat. Even small changes - like swapping soda for sparkling water, or white rice for barley - make a measurable difference.

The Three Are Connected - Not Coincidental

Waist size, triglycerides, and glucose control aren’t separate issues. They’re three sides of the same coin: insulin resistance. Belly fat triggers it. High triglycerides are a byproduct of it. High glucose is the result. You can’t fix one without addressing the others.

That’s why treating just the numbers - like popping a statin for high cholesterol or a pill for high blood sugar - doesn’t work long-term. If the root cause - visceral fat and insulin resistance - isn’t tackled, the other problems come back. Studies show that even if you take medication to lower triglycerides, if your waist doesn’t shrink, your heart risk stays high.

The best tool we have? Weight loss. Losing just 5-10% of your body weight can:

- Reduce waist size by 10-15%

- Lower triglycerides by 20-50%

- Bring fasting glucose down into the normal range

- Improve blood pressure

- Boost HDL (good cholesterol)

It’s not magic. It’s biology. When you shrink fat cells, they stop flooding your system with inflammatory signals. Your liver calms down. Your pancreas gets a break. Your muscles start responding to insulin again.

What Actually Works to Reverse It

There’s no pill that reverses metabolic syndrome. But there are proven lifestyle changes that do - and fast.

Move more, sit less. Aim for 150 minutes of brisk walking a week - that’s 30 minutes, five days a week. But don’t stop there. Stand up every 30 minutes. Take the stairs. Walk after dinner. Movement after meals is one of the most powerful tools for lowering blood sugar.

Change what’s on your plate. Focus on whole, unprocessed foods: vegetables, legumes, whole grains, nuts, seeds, lean proteins, and healthy fats like olive oil and avocado. The Mediterranean diet has been shown to cut heart events by 30% in high-risk people. Why? It’s low in added sugar and refined carbs, high in fiber and antioxidants.

Ditch the sugar. Liquid sugar - soda, sweet tea, energy drinks, flavored yogurt - is the biggest driver of triglycerides and insulin resistance. One 12-ounce soda can raise triglycerides by 30% within hours. Cut it out, and you’ll see changes in weeks.

Limit alcohol. Alcohol is metabolized like sugar by the liver. Two drinks a night can push triglycerides into dangerous territory, especially if you already have belly fat.

Sleep and stress matter. Poor sleep raises cortisol, which increases belly fat and insulin resistance. Chronic stress does the same. Aim for 7-8 hours a night. Try breathing exercises, walks in nature, or journaling. These aren’t "nice-to-haves" - they’re part of the treatment plan.

When Medication Might Help

Lifestyle is the foundation. But sometimes, you need help getting there.

Metformin is the most common drug used for prediabetes. It doesn’t cause weight loss directly, but it helps your body use insulin better - which makes it easier to lose weight. Fibrates or prescription omega-3s may be used if triglycerides are above 500 mg/dL. Blood pressure meds like ACE inhibitors are often needed, but they don’t fix the root cause.

The key is to use medication as a bridge - not a crutch. Once you start losing weight and improving your diet, many people are able to reduce or stop meds. That’s the goal: not lifelong drugs, but restored health.

What’s Next? The Future of Metabolic Health

Researchers are now looking beyond the five traditional markers. A new tool called the TyG index - which combines fasting triglycerides and glucose - is showing promise as a simple, low-cost way to estimate insulin resistance without fancy tests. Some labs are even testing gut bacteria patterns linked to metabolic syndrome.

But the biggest challenge isn’t science. It’s access. Too many people don’t know their waist size, triglycerides, or fasting glucose. Primary care doctors often don’t measure waist circumference - even though it’s the strongest predictor. And insurance rarely covers preventive lifestyle coaching.

The good news? You don’t need a doctor’s order to start. Measure your waist today. Get your next blood test. Look at your numbers. If two or three are out of range, don’t wait. Don’t assume it’s "just aging." This is reversible. With the right changes, you can reset your metabolism - even if you’re 60, 70, or older.

Metabolic syndrome isn’t a life sentence. It’s a sign - a clear, measurable signal - that your body is asking for help. Listen to it. Start small. Move more. Eat real food. Sleep better. Your future heart, liver, and pancreas will thank you.

Can you have metabolic syndrome without being overweight?

Yes. Some people have normal BMI but carry excess fat around their organs - a condition called TOFI (thin outside, fat inside). This is common in people who eat a lot of refined carbs and sugar, even if they don’t look heavy. Waist circumference is a better indicator than BMI for metabolic risk.

How quickly can metabolic syndrome improve with lifestyle changes?

Significant improvements can happen in as little as 4-8 weeks. Triglycerides often drop by 20-50% when sugar and alcohol are cut. Fasting glucose can normalize with consistent movement and better food choices. Waist size may shrink by 1-2 inches in a month with daily walking and portion control. The body responds fast when you remove the triggers.

Is metabolic syndrome the same as prediabetes?

No. Prediabetes means your blood sugar is high, but not high enough for diabetes. Metabolic syndrome includes prediabetes plus two other risk factors - like high waist size and high triglycerides. Most people with prediabetes have metabolic syndrome, but not everyone with metabolic syndrome has prediabetes yet. Still, both mean high risk for type 2 diabetes and heart disease.

Do I need medication to fix metabolic syndrome?

Not usually. Lifestyle changes are the most effective treatment - and often enough to reverse it entirely. Medications like metformin or fibrates may be used short-term to help you get started, especially if your numbers are very high. But the goal is to reduce or eliminate meds through weight loss, diet, and activity. Drugs treat symptoms; lifestyle treats the cause.

Can metabolic syndrome come back after it’s reversed?

Yes - if you return to old habits. Metabolic syndrome is reversible, but not cured. If you regain weight, especially belly fat, or start eating processed foods and sugar again, the markers will return. Long-term health depends on keeping the changes you made. Think of it like brushing your teeth - you don’t stop after one cleaning.

Evan Smith

January 9, 2026 AT 11:17So let me get this straight - you’re telling me I can’t have my morning donut and my soda and still not turn into a walking heart attack? Radical.

Joanna Brancewicz

January 9, 2026 AT 23:07Visceral adiposity drives insulin resistance via TNF-alpha and resistin upregulation - it’s not just fat, it’s endocrine dysfunction.

Lois Li

January 11, 2026 AT 11:54I didn’t know waist size mattered more than the scale. I’ve been measuring my hips for years. Time to grab a tape measure and stop lying to myself.

Also, my grandma used to say ‘if you can pinch it, it’s trouble.’ Turns out she was a scientist without a lab coat.

Ken Porter

January 13, 2026 AT 04:30Another liberal health panic dressed up as science. Next they’ll say breathing causes obesity. Just stop eating carbs if you’re fat - problem solved. No need for all this jargon.

swati Thounaojam

January 14, 2026 AT 05:44In India, we see this young people - skinny but belly big. Sugar tea, pizza, no walk. Doctor say waist 80cm = danger. But no one listen. We think ‘thin = healthy’.

Luke Crump

January 14, 2026 AT 21:59What if the real problem isn’t fat… but the industrial food complex? Who profits from your insulin resistance? Who sells you the pills to ‘fix’ what they created?

We’re not broken - the system is. And they want you to believe it’s your fault for eating too much pizza.

Manish Kumar

January 15, 2026 AT 06:29Let’s think deeper here. Metabolic syndrome isn’t just a medical condition - it’s a mirror of our cultural collapse. We’ve replaced rhythm with convenience, nourishment with stimulation, stillness with screens. The body doesn’t lie - it just screams in biochemistry when we ignore its language. The waist isn’t the problem - it’s the symptom of a civilization that forgot how to be human. We don’t need more data. We need meaning. We need to slow down. To breathe. To eat with presence. To move not for fitness, but for joy. When we do that, the numbers fix themselves. The body remembers how to heal - if we just stop interfering with our own survival instincts.

Aubrey Mallory

January 16, 2026 AT 11:13Ken, your comment is dangerously ignorant. This isn’t about ‘just eating less’ - it’s about systemic neglect, food deserts, and corporate manipulation of nutrition science. People don’t choose obesity like they choose a TV show. If you’ve never had to choose between rent and fresh vegetables, maybe don’t lecture.

Dave Old-Wolf

January 18, 2026 AT 01:04I’ve been tracking my waist for 6 months. Went from 41 to 36 inches. Triglycerides dropped from 280 to 110. Fasting glucose went from 112 to 88. No meds. Just walking after dinner, cutting out soda, and eating more veggies. It’s not magic - it’s consistency.

Also, I used to think ‘skinny’ meant healthy. Turns out I was TOFI. Who knew?

Prakash Sharma

January 19, 2026 AT 01:01Western medicine is obsessed with numbers. In India, we’ve known for centuries - sugar and inactivity kill. But now even our youth are drinking Coca-Cola and sitting on phones. The solution? Return to roti, dal, and walking. Not some American diet plan with kale smoothies.

Donny Airlangga

January 20, 2026 AT 02:28My dad had metabolic syndrome. He lost 20 pounds in 3 months by walking 10k steps daily and swapping soda for water. He’s off all meds now. He’s 72. And he’s the healthiest he’s been since he was 40.

It’s never too late.

Molly Silvernale

January 20, 2026 AT 04:42Insulin resistance… the silent symphony of cellular betrayal… the body’s quiet, screaming plea for mercy… when fat cells become traitors, spewing cytokines like venomous poets… and glucose… oh, glucose… the golden poison, dripping from every soda can, every croissant, every ‘healthy’ granola bar… we didn’t lose control - we were seduced by sweetness… and now, the body remembers… it remembers… it remembers…

Kristina Felixita

January 20, 2026 AT 20:18I’m so glad this post exists. I used to think if I wasn’t ‘fat’ I was fine. Then I measured my waist - 37 inches. I’m 5’4”, weigh 130, eat ‘healthy.’ Turns out, I’m TOFI. Started walking after dinner, swapped white rice for quinoa, and cut out juice. In 6 weeks, my triglycerides dropped 40%. I feel like I’m 25 again.

Don’t wait for a diagnosis. Measure your waist today. It’s the most important number you’ll ever check.

christy lianto

January 21, 2026 AT 19:05Just started this. Cut soda. Walked 20 mins after dinner. Measured waist - down 1.5 inches in 10 days. I didn’t think tiny changes would matter. They do. I’m not ‘fixing’ myself - I’m listening. And for the first time in years, I feel like my body and I are on the same team.