Kidney Stone to Kidney Cancer Risk Calculator

Your Risk Assessment

Risk Factors Explained

Stone Episodes

Each additional episode increases cancer risk due to cumulative inflammation and tissue damage.

Stone Type

Calcium oxalate stones are most strongly associated with increased RCC risk.

Sodium Intake

High sodium diets contribute to both stone formation and cancer risk.

Hydration

Adequate fluid intake helps prevent stones and may reduce cancer risk.

Quick Take

- Large‑scale studies show a higher odds of advanced renal cell carcinoma (RCC) in people with a history of kidney stones.

- Calcium‑oxalate stones release inflammatory by‑products that can damage kidney tissue and promote tumor growth.

- Patients with recurrent stones should discuss imaging and biomarker testing with their urologist.

- Lifestyle changes that lower stone risk - adequate hydration, reduced sodium, and balanced calcium - may also cut RCC risk.

- Research is still exploring whether the stone‑cancer link is causal or a shared risk profile.

What Are Kidney Stones?

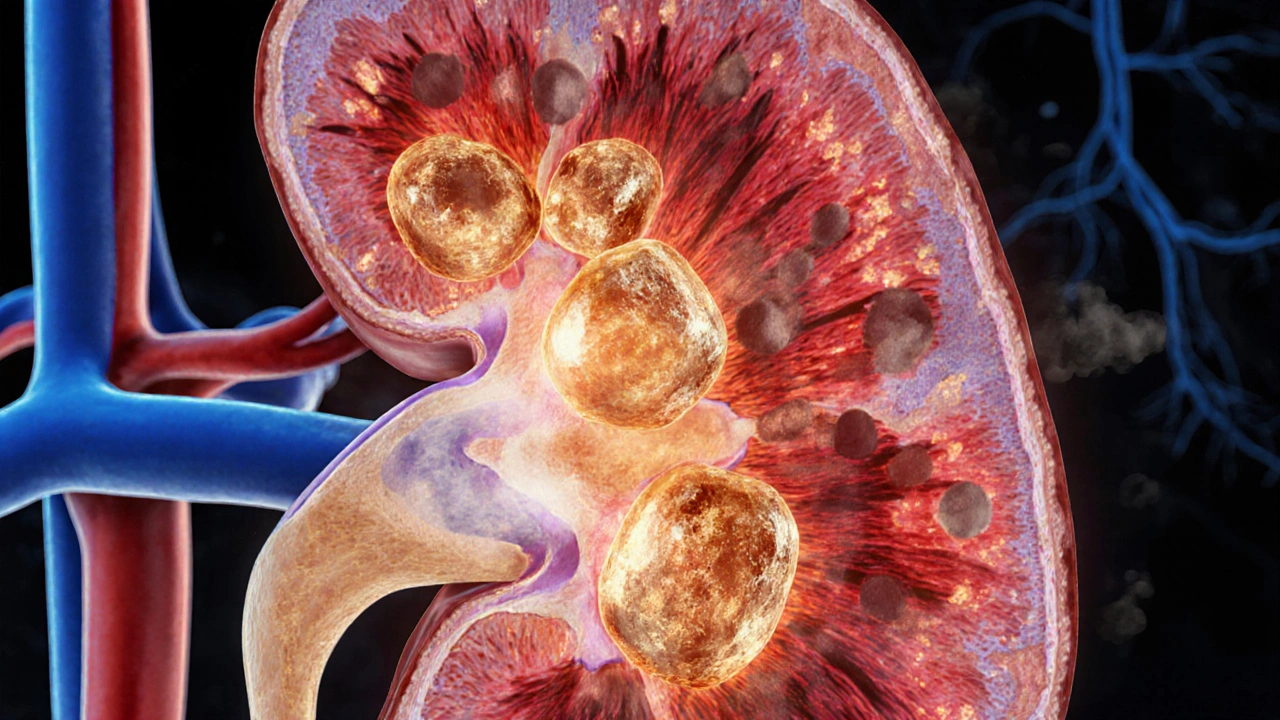

When you hear Kidney Stones are hard mineral deposits that form inside the kidney's collecting system, the first image is often of excruciating pain. Most stones are made of calcium oxalate, a crystalline compound that precipitates when urine becomes supersaturated with calcium and oxalate ions. Other types include uric acid, struvite, and cystine, each linked to different metabolic or infectious triggers.

Beyond the sharp pain, stones can cause chronic inflammation, scarring, and even loss of kidney function if they’re not managed. Over the past decade, epidemiologists have started to notice a pattern: people with a prior stone episode seem to develop kidney cancer more often, especially the clear‑cell subtype that makes up about 75% of RCC cases.

Understanding Advanced Renal Cell Carcinoma

Renal Cell Carcinoma is the most common form of kidney cancer, arising from the renal tubular epithelium and typically classified by stage (I‑IV) and grade. “Advanced” RCC usually means stage III or IV disease, where the tumor has grown beyond the kidney capsule or spread to distant sites such as the lungs, bones, or liver.

Clear‑cell RCC, the dominant histology, often harbours mutations in the VHL gene, leading to uncontrolled angiogenesis. Prognosis drops sharply once the disease is metastatic, with five‑year survival rates falling under 15% compared to 90% for early‑stage tumors.

Epidemiological Evidence of a Stone‑Cancer Link

Large cohort studies from the United States, Europe, and Asia have repeatedly reported a 1.3‑ to 2.0‑fold increase in RCC risk among stone formers. A 2023 meta‑analysis of 12 prospective studies (over 1.6 million participants) found that a history of kidney stones raised the odds of developing RCC by 46% (OR=1.46, 95%CI1.28‑1.66). The association grew stronger when the analysis focused on advanced-stage disease.

Why does the link appear strongest for advanced RCC? One theory is that chronic inflammation caused by stones may create a microenvironment that fuels malignant transformation and progression. Another angle looks at shared risk factors - obesity, hypertension, and high dietary sodium - that simultaneously drive stone formation and tumor growth.

Biological Mechanisms Connecting Stones to Cancer

Three main pathways have earned the most attention:

- Inflammatory Cascade: Calcium‑oxalate crystals trigger the NLRP3 inflammasome in renal tubular cells, releasing interleukin‑1β and tumor necrosis factor‑α. Persistent inflammation can lead to DNA damage, epigenetic changes, and a pro‑angiogenic milieu favorable for cancer cells.

- Oxidative Stress: Crystal‑induced injury generates reactive oxygen species (ROS). ROS can oxidize nucleic acids and proteins, facilitating mutagenesis. In animal models, rats fed a high‑oxalate diet showed increased 8‑oxoguanine lesions in renal tissue, a marker of oxidative DNA damage linked to carcinogenesis.

- Microbiome Alterations: Stone formers often harbor urease‑producing bacteria (e.g., Proteus) that raise urinary pH, encouraging struvite stone growth. These bacteria also produce endotoxins that may influence systemic immune responses and, indirectly, tumor surveillance.

While each pathway alone doesn’t prove causality, together they paint a plausible picture of how recurring stones could set the stage for malignant change, especially in genetically vulnerable kidneys.

Clinical Implications: Screening and Management

Given the data, many urologists now ask stone patients about personal or family history of cancer. If a patient has had more than two stone episodes or presents with a large stone (>1cm), a low‑dose CT scan of the abdomen can simultaneously assess stone burden and look for suspicious masses.

CT Scan provides high‑resolution, cross‑sectional images that can detect both stones and early renal masses is preferred over plain X‑ray because it can pick up tumors as small as 5mm. If a mass is identified, a biopsy or partial nephrectomy may be indicated, depending on size and location.

Beyond imaging, emerging blood and urine biomarkers-such as circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) and urinary aquaporin‑1-are being evaluated for early RCC detection in high‑risk stone formers. While not yet standard of care, enrolling patients in clinical trials could give them access to cutting‑edge surveillance.

From a preventive standpoint, the same lifestyle tweaks that lower stone risk also reduce RCC risk: drink enough water to produce at least 2L of urine daily, keep sodium intake below 2,300mg, maintain a healthy BMI, and limit animal protein. For those prone to calcium‑oxalate stones, a moderate calcium intake (1,000‑1,200mg) from food rather than supplements is advisable, as dietary calcium binds oxalate in the gut and prevents its absorption.

Research Gaps and Future Directions

Despite the mounting evidence, several questions remain:

- Is the stone‑cancer relationship merely correlational, or does stone removal lower subsequent RCC risk?

- Do specific stone compositions (e.g., uric acid vs. calcium oxalate) confer different levels of cancer risk?

- Can targeted anti‑inflammatory therapies after stone episodes interrupt the carcinogenic cascade?

Large prospective trials that randomize stone patients to aggressive surveillance versus standard care could answer the first question. Meanwhile, metabolomics studies are dissecting urine signatures that might predict which stone formers are also on a tumor‑prone trajectory.

On the genetics front, the VHL Gene regulates hypoxia‑inducible factors and is frequently mutated in clear‑cell RCC. Some investigators are exploring whether stone‑induced hypoxia in renal tissue creates selective pressure that favors VHL‑mutant clones, effectively accelerating tumor development.

Bottom Line for Patients

If you’ve ever battled kidney stones, it’s worth having a conversation with your doctor about cancer screening, especially if stones keep coming back. Staying hydrated, watching your diet, and getting regular imaging when indicated can catch both problems early. While the link isn’t 100% proven, acknowledging the risk gives you a chance to act before a tumor gets out of control.

| Factor | General Population Risk | Recurrent Stone Patients Risk | Relative Increase |

|---|---|---|---|

| Obesity (BMI≥30) | 1.5‑fold RCC risk | 2.3‑fold RCC risk | ≈1.5× |

| Hypertension | 1.3‑fold RCC risk | 1.8‑fold RCC risk | ≈1.4× |

| High Sodium Diet | Modest increase | Significant increase (OR≈1.6) | ≈1.6× |

| Calcium‑Oxalate Stones | Baseline | 1.5‑2.0‑fold RCC risk | ≈1.7× |

Frequently Asked Questions

Do kidney stones cause kidney cancer?

Current research shows a strong association but not definitive causation. The inflammation and oxidative stress from repeated stones may create a fertile ground for cancer cells, especially in people with other risk factors.

How much does the risk increase after a stone episode?

Meta‑analyses report a 30‑50% higher odds of developing renal cell carcinoma, and the increase is higher for advanced-stage disease-up to a two‑fold rise in some studies.

Should I get a CT scan after a stone passes?

If you have recurrent stones, a low‑dose CT scan can both confirm stone clearance and screen for small renal masses. Discuss the benefits and radiation exposure with your urologist.

Are there blood tests that can detect early kidney cancer?

Researchers are evaluating circulating tumor DNA and specific protein markers like aquaporin‑1, but these tests aren’t yet part of routine screening.

Can lifestyle changes lower my combined risk?

Yes. Drinking enough water, limiting sodium, maintaining a healthy weight, and eating a balanced diet reduce both stone formation and RCC risk.

Gus Fosarolli

October 4, 2025 AT 05:17At least now I have a legit excuse to drink more water. And maybe stop pretending I ‘forgot’ my electrolyte tablets.

Evelyn Shaller-Auslander

October 5, 2025 AT 11:00John Power

October 6, 2025 AT 17:17And if you've had more than one stone? Talk to your doc. Don't wait until you're in pain again.

Richard Elias

October 8, 2025 AT 01:51Scott McKenzie

October 9, 2025 AT 09:11Got my first low-dose CT last year - found a 6mm spot. Turned out benign. But if I hadn’t pushed for it? Who knows?

Hydration + low sodium = my new religion. Also, stop eating spinach like it’s kale. 🥬🚫

Jeremy Mattocks

October 9, 2025 AT 09:12Paul Baker

October 9, 2025 AT 15:49Zack Harmon

October 9, 2025 AT 19:14Drink distilled water. Avoid all calcium. And pray.

Jeremy S.

October 11, 2025 AT 12:09Jill Ann Hays

October 12, 2025 AT 22:12Mike Rothschild

October 12, 2025 AT 23:30Ron Prince

October 14, 2025 AT 20:57Sarah McCabe

October 15, 2025 AT 10:14King Splinter

October 15, 2025 AT 16:58Kristy Sanchez

October 16, 2025 AT 17:38And now I’m supposed to drink water like it’s my job? I’m already crying just thinking about it.

Michael Friend

October 18, 2025 AT 06:15Jerrod Davis

October 20, 2025 AT 02:59Dominic Fuchs

October 20, 2025 AT 17:12